The Awakening by Shruthi Rao

One morning, Venkatesh decided to wear his wife's salwar-kurta. One moment saw him sitting on the sofa, reading the newspaper, and the next moment, he was standing in front of his wife's cupboard, fingering her clothes.

A purple set caught his eye, the colour of the smoky blossoms of the jacaranda across the road. He took out the salwar, kurta and dupatta from the almirah and laid them out on the bed, one next to another. The dupatta was particularly pretty, like the carpet the purple flowers made on the ground before the morning traffic crushed them into the tarmac.

Venkatesh took off his t-shirt and dhoti. He picked up the salwar first, and put it on. This was like his drawstring pyjamas, except that it was of a soft material that tickled his thighs. Then he slipped the kurta over his head and looked at his own reflection in the full-length mirror on the almirah. It was longer than his khadi kurta. This kurta's neck was round and large. His clavicle stuck out. And the dress hung loose on him as if from a coat hanger.

He frowned before he remembered. Of course, he had no breasts...

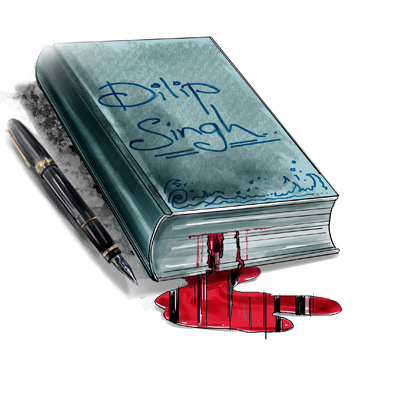

The Sad Unknowability of Dilip Singh by Tanuj Solanki

The never-to-be-famous writer Dilip Singh died of his own hand in the winter of two thousand and six. He was twenty-nine. His mother returned from her grocery rounds on the unfortunate day of his death and found him hanging from the ceiling fan, one of her plain widow's saris wrapped tightly around his strained neck. In the hope that her son still had some life in him, she drew a chair (the same chair that Dilip had toppled earlier) beneath his feet and mounted another to untie the noose. Failing to do that, she noticed the loosened plaster around the hook that held the ceiling fan, and in her panic she began to pull the body downward. Some plaster and cement fell on her face, but the body could not be set free. It never occurred to her that had she managed to free it, the heavy ceiling fan, which was from an era when it was made of metal, would have crushed them both.

Dilip's choice wasn't something that the circumstances, or my understanding of them, added up to. To say that he was a writer is not to say much, for the label is a problematic one...

Birdwatcher by Monika Pant

Siddharth stepped back after an hour at the telescope. The pale cream wall with the framed photographs was unchanged. So was the streak of dampness that ran from the ceiling in the far corner. The indoor world was the same as always.

He packed away his instruments, his camera, his sketches and closed the window. His rucksack lay at the side of his bed. With a sigh he picked it up and left the house to answer his father's summons. A few hours later, he was in the city, speeding through in a black and yellow taxi. But when the streets narrowed down, they began to move more and more slowly. He could see the sweet shops, the cups of tea held by people and the pushing, elbowing men and women who always seemed to want to go somewhere. There were loosely strung groups of boys standing with hands on their hips or around the shoulders of others, their faces a blur, their eyes unfocused, their teeth bared in raucous laughter. He stared at them and at the buildings with blackened sides that had been whitewashed over and over again, and at the new ones, all glass and chrome, their tops chopped off by the frame of his taxi window.

His ears felt rather than heard the mangled mix of screeching tyres, rattling buses, purring cars, the incessant talking, the shouts, and the horns, the merciless horns laying claim to the atmosphere as though it belonged to them. A patriotic song from a teashop mixed inharmoniously with a cell phone singing 'You're my Hunny-Bunny' and 'Chikni Chameli' from somewhere juxtaposed with the blaring-out of the latest manifesto from a politico who was standing for the municipality elections next week. Already he was longing to go back...

The Old Woman Who Could Fly by Deepak Unnikrishnan

Big-Shot Bhaskar knew what he was doing when he built the first nursing home in Trichur. He called it 'Gulf Party Peoples'. This was the early eighties. Families, especially matriarchs, would walk by the place in order to giggle at the lone sentry in uniform, some foreign fellow from somewhere whose job it was to stand at attention outside the building site. Bhaskar wasn't in a hurry to do more hiring. In a few years, he said. Fool's gone mad, everyone said. But I went to school with Bhaskar. The boy's brain was a crystal ball loaned to him by the devil himself. Early on, he'd calculated that geriatrics needing care would constitute the biggest market in Gulf-addicted NRI-obsessed Kerala. He was right. When I put my own mother in there, she'd been the last one holding out. Everyone else over the age of sixty had been cajoled, coerced, and convinced into locking up or subletting or selling their homes and moving into Big-Shot's Gulf Party Peoples. When family came to visit, these men and women representing various positions of familial authority were escorted by sons and daughters to locked homes which were unlocked for the duration of their visit, before being returned to the nursing home weeks (or days) later. Frankly, if you had someone in there, like I did, it was an excellent arrangement...

Shifting Lives by Ajay Patri

The red mud underneath her feet is getting thicker by the day. The late rains do not have the strength to pierce through and settle on the surface, making the mud slushy. She wades through it with difficulty and upon reaching the field, picks up a bent stick lying on the ground and scrapes the layer of mud that cakes the soles of her bare feet. She looks up in time to witness Father looking at her with a frown on his weathered face. He doesn't say anything and turning away from her, goes on to join the others.

She hears rumours that she pays little attention to. The yield is disappointing, the weather unpredictable. The soil, which has seen them through so many years has now become stubborn. It has turned on them, choking the roots of the plants they depend on for their livelihood. There is little else to do but move on.

She remains aloof from such discussions but even in her aloofness, she knows that the basest of rumours have their origins in a tiny kernel of truth.

It is a warm night when Father brings up the rumours for the first time in their hut. He doesn't make a fuss of it, saying it while spooning the steaming potato gruel into his mouth rapidly, like he is talking about a sore leg.

We may have to leave this place soon...